The problem of machine translation

As language teachers, it seems that every day we have to battle the pernicious force of machine translation (MT). In 1997, Alta Vista launched Babelfish, one of the first web-based interfaces for MT. Twenty years later, it seems like every web portal, social network, and search engine offers some kind of automatic translation tool. Even LINE, the kawaii messaging service ubiquitous in Japan, offers an instant translation function, which behaves just like regular chat.

But despite its apparent popularity, and arguable usefulness as an assistive tool to human translators, MT is not a helpful technology for language teachers or learners. It is at best a nuisance, and at worst strongly detrimental to students’ second language acquisition.

The main problems with MT with regard to language pedagogy are that:

- It is inaccurate, especially for idiomatic expressions; and

- It negates students’ opportunities for language learning

The first of these problems can be easily observed when typing any reasonably idiomatic expression into Google Translate, perhaps the best free web-based MT available right now. Unfortunately, as we shall see, that’s not saying very much..

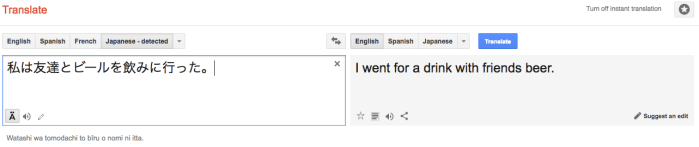

Exhibit 1

In this example we see the translator mess up the word order, and also render the verb “drink” as the noun “drink”. “I went to drink a beer with friends” is the more natural human-produced translation for this sentence.

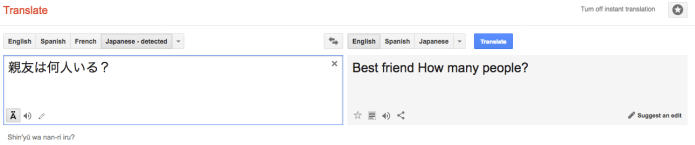

Exhibit 2

In this example, again, the word order is completely jumbled, and the singular “best friend” doesn’t make sense when the question requires a plural response. Once again, the human generated translation is far superior: “How many close friends do you have?”.

I won’t labor the point here, but you can do your own experiments with any of the currently available MT tools, and you will inevitably come to the same conclusion: MT is still quite bad. Although it can usually convey the gist of the input sentence, it clearly lacks eloquence, idiomaticity and accuracy.

What to do about it

Having concluded that MT is not a good pedagogical tool, the question arises as to how we can eliminate its use both inside and outside the language classroom.

Ban smart phones in the classroom?

Within the classroom, you could prevent the influence of MT by banning smart phones entirely. But if you do this, you are indiscriminately blocking off more fruitful avenues to autonomous learning, along with many other positive affordances offered by mobile devices.

Automatic MT detection

Outside the classroom, your power over students is limited, especially over those more inclined to take the “easy” option of MT in the first place. In addition, although we may strongly suspect a student of using MT outside class, it is often difficult to prove. Although progress is being made in developing MT detection tools, it is still nascent technology. Most of the solutions available at the moment require both the source and translation text in order to attempt to detect MT.

Manual MT detection

It can be possible, however, to manually detect and prove machine translation if you have a working knowledge of your students’ L1.

In a recent low-level speaking class, I asked students to record and transcribe their answers to a 1-minute speaking task. One student’s answer seemed suspiciously like “translationese”. One sentence in particular stood out: “Mother of rice is very delicious”. I guessed that the student had tried to translate the Japanese sentence “お母さんのご飯はとても美味しい” which would be more naturally rendered as “My mother’s rice is very tasty” or more idiomatically as “My mother makes very good rice”.

After inputting my hypothesis into Google Translate, I was presented with the exact same broken English as the student had used in his report. He was well and truly “busted”!

Eliminate coursework

Of course, detecting and subsequently proving the use of MT for a pile of 20 or 30 written reports is a huge waste of time. However, because the temptation to use MT, especially for low-level, low-motivation students is so high, simply instructing students not to do so can be ineffective.

The use of MT became so prevalent with one of my lower level writing classes, that I decided to eliminate coursework altogether, and administer every written assessment in exam conditions. This was the only way I found that I could guarantee that students were not using MT in their written assignments.

Highlight the inadequacy of MT

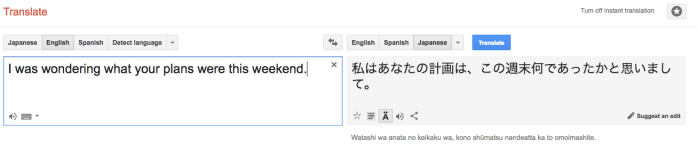

An alternative solution for more highly motivated classes (those that actually care about developing their English accuracy and idiomaticity) is to highlight how bad MT can be, and in the process hopefully dissuade them from using it all together. One way to do this is to input some English phrases into an MT tool, and translate them into your students’ L1. Students will then understand in a more direct way how bad some of the translations can be.

Conclusion

One day, machine translation may be accurate enough to make language teachers redundant, along with translators, interpreters, subtitlers, and a host of other language-related professions. It may cause an industry shake-up as far-reaching as self-driving cars. But that day is unlikely to be any time in the near future, despite how far we’ve come in recent years. The current generation of MT tools often produce inaccurate and unidiomatic translations. MT is unhelpful for English language pedagogy, and steps should be taken to detect and prevent students’ use of MT.